I’ve been sent lots of interesting books lately, but haven’t had time for a close reading of any of them. Still, this is Web 3.0, and I’m confident that even a superficial response from me will be more useful than anything LLMs can offer1.

The Peace Formula by Dominic Rohmer makes a lot of sensible observations about war and peace. Most importantly, as I argued at length in Economics in Two Lessons (agreeing on this point with Hazlitt’s Economics in One Lesson, the idea that war is economically beneficial for society, or even for the capitalist class as a whole, is nonsense. Nevertheless, in the absence of economic security, becoming a warlord’s henchman or joining a guerilla army may be a more attractive route to escaping poverty than trying to produce something useful, only to see it stolen from you. This danger is particularly acute in a country with mineral resources. As Rohmer observes, one of many reasons for encouraging the green energy transition is that it reduces the power of warlords who rely on resource revenue.

Unfortunately, the book was written before the 2024 election, at a time when it seemed that Trump might be a thing of the past. The slide of the US into kleptocratic dictatorship, following the path of Russia and China, means that peace is likely to be a long way off. Still, it’s worth reading and thinking about what a better world might look like when our current afflictions pass.

As regular readers will know, I’ve been very critical of pro-natalism, the idea that society should encourage or pressure women to have more babies, in order that global or national populations can continue to rise. One problem I’ve had is that the idea has become so dominant that many dubious assumptions are taken for granted. I was please therefore to receive a copy of After the Spike a comprehensive statement of the case for pronatalism by Dean Spears and Michael Geruso.

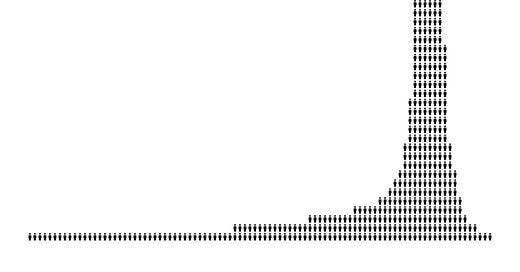

Cover design showing the rise and projected fall of world population

The title refers to the fact that, if fertility remains below replacement level (one surviving daugher per woman), the massive growth in world population since about 1800 will go into reverse, perhaps leading to a population of only 2 billion around the year 2400. Unlike the authors, I’m not bothered by this. Almost all of the technological progress of the 20th century was generated in a group of rich countries (roughly the OECD) with a total population of less than 1 billion. And except for some raw materials found only in poor countries, the OECD was effectively self-sufficient. So, a population of a billion would be perfectly sustainable, as well as leaving room to rewild much of the world. That couldn’t continue indefinitely, but I’m much more concerned about ensuring that humanity survives in any form to 2400 than I am about what might happen to global population after that. I’ll have plenty more to say on this and so, I expect will Spears and Geruso.

Matthew Adler’s Risk, Death, and Well-Being: The Ethical Foundations of Fatality Risk Regulation is important, but is written for a relatively limited group of specialists. The central assumption is that policy on fatality risks should be designed, as far as possible, to maximise a social welfare function, which is in turn determined by the welfare of each of the individuals in the society in question. The main choice is between utilitarianism and prioritarianism (weighting outcomes by positions in the income distribution). For individual decisions this maps into the choice between expected utility (the usual model) and rank-depenendent utility (which I developed in the early 1980s and was later incorporated into the Prospect Theory of Kahnemant and Tversky. Adler’s approach takes for granted that policy should be consequentialist; that is, concerned with outcomes rather than with process (except to the extent that adherence to good processes tends to produce good outcomes). I’m happy with that view, but others may not be.

The book is available on an open access basis here

Probably of most interest to my readers is Graeme Turner’s Broken: Universities and the Public Good which was published a few days ago, but has been running in extract form in lots of places. Much of it has been concerned to document the way in which the university sector has been converted from a diverse and vibrant, if chaotic, set of idiosyncratic institutions to homogeneous a neoliberal blob, pretending to be competitive while offering the same unsatisfactory product to everyone. The results for academic morale are well known, as is the state of constant conflict between the university sector and the national governments that provide most of the funding I’ll do a proper review later. In the meantime, I’ll take the opportunity to do the common, if annoying, “this is what I wish the author had said” thing.

In repsonse to this depressing situation, Turner argues that universities should be recognised as an essential public service, like schools and hospitals. I agree, but take this point to its logical conclusion. If unis are an essential public service, they should be run like one, as a responsibility of government rather than as a collection of notionally independent quangos (in the original meaning of quasi-NGOs). The federal minister should be responsible for universities in the same way that state ministers are responsible for public schools (this implies scrapping the vestigial role of state governments as the legal authorities under which unis were established. I’ve made this point at greater length here.

Second, like everyone else Turner is worried about the effects of ChatGPT and other LLMs. For practical purposes, these make most forms of assessment useless for the purpose of grading students. Closed book exams are still feasible, but they are pedagogically awful. My solution is to bite the bullet and give up on high-stakes assessment. Within the university, assessment can be used to give feedback to students on their progress, strengths and weaknesses and so forth, and advice on whether they are ready progress. Employers can make their hiring decisions without university grades, as they already do for workers with even minimal experience. If they want high-stakes tests, they can organise pay for them.

This leaves the question of how we can motivate adolescents/young adults to work without the carrot and stick of marks. My partial answer is that we should make at least one “gap year” the norm, with the expectation that this will include some full-time paid work. Once they have had this experience, most young people will have a better idea of what they can gain from improving their skills. Others will find that they can do just fine without university. That’s only one suggestion, but I’m sure we can find more, once we get away from the ingrained idea that grading is an essential part of the mission.

Meanwhile, for my theoretical work on decision theory, I’m pushing slowly through books on Heyting algebras (Esakia), Stone spaces (Johnstone) and (always scary for me) Category theory (Simmons). If anyone wants to read my thoughts on these topics, they will probably turn up on arxiv, or you can email me and I will send you something when (if) it’s done.

Follow me on Bluesky or Mastodon

Read my comic book presentation of The Perils of Privatisation. Paid subscribers get a free physical copy.

Read my newsletter

I tried ChatGPT on the Rohmer book. Its response would work fine as a mildly generic blurb, but didn’t offer more than an effusive summary of key points. On the other hand, the bot took two minutes, whereas I had to read the book and write the review. I’m fast, but not that fast.

"i’m pushing slowly through books on Heyting algebras (Esakia), Stone spaces (Johnstone) and (always scary for me) Category theory (Simmons).."

Have you tried asking a chatbot for summaries in the format of comic books?

Hi John. I have not read either “Economics in Two Lessons” or “Economics in One Lesson” nevertheless, as an uneducated casual observer of stuff, the following statement made absolutely no sense to me, “the idea that war is economically beneficial for society, or even for the capitalist class, is nonsense.”

I used my preferred AI to compile some numbers, for the period 2022 to 2024, and it produced the following summary of major corporations in the US military Industrial complex, I added in Palantir for its use of AI for target acquisition.

Profit Growth Stock Growth Top Revenue Source

Lockheed +40% +47% F-35 jets, missiles

Raytheon +25% +28% Patriot missiles, engines

General Dynamics +33% +52% Tanks, submarines, shells

Palantir +370%* +100% AI warfare (Ukraine/Israel)

* From loss to profit.

I would wager that neither the war in Ukraine, or Israel’s several conflicts in West Asia would still be ongoing if the 1 percenters and ten percenters investing in wars were not making a motza.

The wars in Europe and Palestine have severely diminished the US stockpile of 155mm artillery shells, with over 3 million supplied to Ukraine. The pentagon has asked General Dynamics to increase production from 28k to 100k shells per month.

I am certain that GD will be making a substantial profit from those sales, and one can only imagine what is happening to the market for large industrial and warehousing premises with GD seeking suitable locations to install the plant required.

Are these figures not evidence that, at least some in the investing class are profiting from never ending wars?