I wrote this for a Guardian panel. The published version was cut for space reasons, so here’s the full version

The central concern expressed by the Reserve Bank in defending its high-interest rate policy is that expectations of higher inflation may become entrenched, requiring a further, more painful round of contractionary monetary policy in the future. Even after stripping out the effects of various “cost of living measures”, the RBA’s estimated core inflation rate is only just above 3 per cent. This suggests extreme sensitivity to the risk of even a modest increase in the long run rate of inflation.

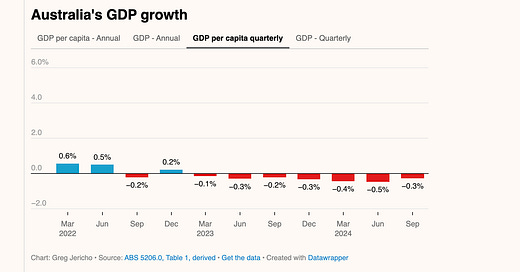

By contrast, the RBA expresses no concern that the reduction in economic growth induced by its policies will lead to a permanent reduction in living standards. The underlying assumption of the RBA’s macroeconomic model is that the economy will always return to a long-run growth path determined by technology and economic structure.

But there is ample evidence, notably from New Zealand and the UK to suggest that the loss in productive capacity associated with slowdowns and recessions is permanent or very close to it. Until the 1980s, the New Zealand and Australian economies grew almost in parallel. But from the early 1990s, onwards, while Australia has avoided recession (at least on the widely-used measure of two quarters of negative growth) for more than thirty years, New Zealand has had at least half a dozen. This miserable performance, reflecting both policy misjudgements and overzealous neoliberal reforms has resulted in New Zealand falling far behind Australia in terms of incomes and living standards. The steady flow of New Zealanders to our shores, and the lack of any comparable flow in the opposite direction, reflects this.

In the UK, the combined effects of the GFC, Conservative austerity policies and Brexit has produced a long period of stagnation in national income. As Brad DeLong observes, had Britain continued on its pre-2008 growth trend it would now be forty percent richer than it is today

Even though Australia has experienced a lengthy period of declining national income per person, the RBA does not even mention the risk of a permanent reduction in living standards. In its pursuit of rapid achievement of an essentially arbitrary inflation target, RBA monetary policy puts all our futures at risk

Read my newsletter

A practical suggestion. At first sight, the CBA is working with the psychology of the 1920s, of Pavlov and Skinner, to estimate a single self-fulfilling variable called “expectations”. Time to update the toolkit to the modern era of Kahneman and Tversky. of prospect theory and behavioural economics. The CBA should spend money on evidence-driven research on what Australians believe is happening to the real economy and prices, and why. The US election brought to light a remarkable and theoretically challenging disconnect between popular and professional opinion in the USA on the matter, and I doubt if Australia is very different.

Favoured hypotheses to explain this gap include: (1) the public are morons; (2) the government statisticians are Deep State liars controlled by lizard men, Soros, etc; (3) Rupert Murdoch; (4) Russian cyberwarfare; (5) the public are using a basket consisting only of gasoline and eggs. If it’s the eggs, one cheap policy option is to make them free.

Central banks by definition have plenty of money and should pay for the highest standards of research, such as survey samples of 10,000 rather than the corner-cutting 1,000 of most political polls, longitudinal studies tracking the same sample, focus groups with passive expert support from people who know where to look up the price of eggs in Adelaide in 2001, the best peer-reviewed number-crunching, and so on.

I read somewhere quite recently that Australia is towards the bottom of an index measuring the complexity of the economy. We're down there with underdeveloped economies. I think that this failure to diversify away from low value commodities based industries has the greatest potential to erode living standards. The timidity of the government in taxing the commodities industries means we have far less to invest in encouraging the development of higher value tertiary industries than we otherwise might. The lack of competition in in key sectors such as transport, food and other consumer goods is a significant factor in having inflation stuck at the current level (which may be now it's 'natural' level as has been pointed out). Wasting vast amounts on flights of fancy like AUKUS instead of investing in people doesn't help.