I don’t think I’m the only one to notice that Marc Andreesen’s ‘Techno-Optimist Manifesto’ has a curiously dated feel, as if the author had been cryogenically frozen around the time he cashed out of Netscape. Two points particularly struck me.

First, there his paean to market processes, which are represented as "Willing buyer meets willing seller, a price is struck, both sides benefit from the exchange or it doesn’t happen”

This statement might have seemed plausible at the height of the dotcom boom, which coincided with the high point of faith in ‘turbo-capitalism’. But it’s not at all descriptive of the way in which the Internet and the World Wide Web have developed, as Andreesen himself ought to remember.

Until the mid-1990s, the Internet and the World Wide Web were products of government funded organizations, developed by academics and other users without a profit motive. The associated software, including Andreesen’s Netscape Navigator were given away free of charge (Gopher, the main rival to the WWW, failed because the he University of Minnesota tried to cash in on it). The Internet rapidly displaced commercial enterprises like AOL (who tried to buy their way back in by acquiring Netscape, and were themselves bought by Time Warner in one of the most disastrous acquisitions of all time). Even after the Web was open to commerce, much of the innovation (blogs, Wikipedia, most recently the Fediverse) came from non-commercial sources.

But even the for-profit Internet doesn’t fit Andreesen’s description. Google, Facebook and other platforms don’t rely on exchanging their services at an agreed price. Rather, they provide a service that is free of charge, and make their money by serving ads and harvesting user data for other marketers. At a stretch, one might say that advertisements in traditional media represent an agreed price “watch 20 minutes of our sitcom, and consume 10 minutes of ads”. But cookies and trackers are surreptitious - no one can really know how much they are paying. We are seeing a gradual shift back towards subscription models, both for traditional media outlets and for new entrants like Substack. But these are the exception rather than the rule.

Hardware vendors like Apple come a bit closer to the traditional market model. But even they rely critically on ‘intellectual property’, that is, laws preventing competitors from supplying equivalent products.

The result of all of this is that, in the Internet economy, there is almost no relationship between contribution and reward. Andreesen is a billionaire while Tim Berners-Lee drove a used car for years (more recently, though, he has been reported as having a net wealth of $50 million). As Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow have pointed out , the crucial thing is to establish a choke-point at which wealth can be extracted. These choke points do more to hinder innovation than to promote it.

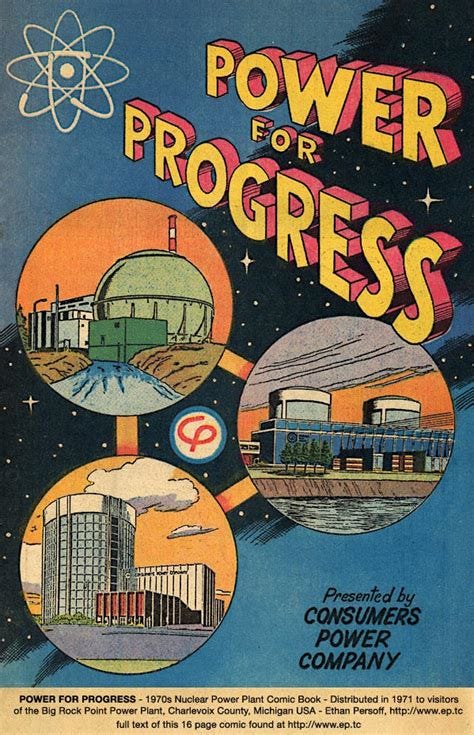

Then there’s his pitch for nuclear fission. Again, this made sense in the late 1990s. The reality of global heating, and therefore the need to stop burning coal was becoming undeniable. Alternatives such as wind and solar were prohibitively costly. So, the risks of nuclear accidents and the problem of managing waste were outweighed by the certainty of climate catastrophe under business as usual.

But in 2023 nuclear power is a dead duck, a C20 technology with a string of failed revivals in C21. New additions have barely kept pace with closures of old plants.

By contrast, solar PV is the biggest single example in support of techno-optimism. From essentially zero, it’s reached the point where annual additions are around 400 GW a year, almost as much as the *total* installed capacity of nuclear. Costs have plummeted and, after some generous initial support from government, most of the process is being driven by markets. There is no better case of creative destruction than the rise of solar PV

Andreesen’s failure to recognise this illustrates two points

• He’s ignorant and doesn’t choose to inform himself, instead gullibly following sources that pander to his confirmation bias

• He’s driven not by rational belief in the progress of technology but by rightwing culture war politics

Finally there’s Andreesen’s rejection of the precautionary principle, which has been endorsed by quite a few generally sensible people, including Daniel Drezner . The precautionary principle has been interpreted in all sorts of different ways, from the common sense of “look before you leap” to the absurdity of “don’t do anything that might go wrong”.

But the most sensible interpretation, and the one relevant to the current debate is that of a burden of proof on innovators (I wrote about this with Simon Grant, here). That is, the precautionary principle, as applied to any particular domain, says that innovators should have to demonstrate in advance that their proposed innovation will not be harmful.

The opposite view, summed up by aphorisms like “move fast and break things” and “better to seek forgiveness than permission”, is that innovation should not be constrained. Negative consequences can be dealt with after the event, and, if necessary, rules can be adjusted to prevent a repetition.

The precautionary principle isn’t universally applicable. There’s widespread (maybe not universal) support for applying it to new medicines, whereas not many people would want to apply it to new restaurant menus (assuming they complied with existing health standards).

Looking at Andreesen’s manifesto, three cases come to mind. First, since he’s now a financier, there is the case of financial innovation. The default here is to allow any innovation that complies with the rules covering existing financial instruments. In my view, this has turned out very badly, most obviously in the leadup to the GFC, but also with more recent innovations like Buy Now, Pay Later, not to mention cryptocurrencies, in which Andreesen is heavily invested.

Then (not mentioned in the manifesto) but maybe in the background there’s the case of genetically modified crops. Here the precautionary principle was applied early on, following the Asilomar Conference on Recombinant DNA. This process allowed research that established, fairly convincingly, that food produced from GM crops was just a safe as that produced using crops developed by traditional breeding and selection (also a form of genetic modification). That finding didn’t end controversy over issues like corporate control, or debate over specific innovations like Roundup-Ready (glyphosate-tolerant) crops, but it gave pretty good assurance that the nightmare scenarios floating around at the time of the initial discoveries would not materialise.

Finally, of course, there are recent developments in Artificial Intelligence, from which Andreesen hopes to make a lot of money. I’m not convinced by the apocalyptic scenarios put forward by people like William McAskill (and linked in some obscure way to the idea of ‘effective altruism’). But I also haven’t seen a clearly convincing counterargument to say that such an apocalypse can’t happen, or, at least, is less of a concern than other risks it might tend to offset, for example by generating enough prosperity to reduce the risk of nuclear conflict. And that’s also true of risks that aren’t existential such as the possibility of large-scale fraud through techniques like voice replication. Following the logic of the precautionary principle, I’d prefer (if possible) to slow down the pace of development and try to understand the consequences before they are irreversible.

None of this makes me a techno-pessimist. But, having seen lots of glowing visions of the future crumble into dust, I’m not impressed by Andreesen’s revival of 20th century tech-boosterism. Scientific progress provides us, collectively, with a range of technological options. The choice between them should be made wisely and democratically, not by the whims of venture capitalists.

"Techno"-optimism? I barely saw a word in Andreesen's essay related to technology. It was all about "tech"--the business of creating monopolistic choke-points. It isn't hard to be a technology optimist and a tech pessimist.

“Scientific progress provides us, collectively, with a range of technological options. The choice between them should be made wisely and democratically, not by the whims of venture capitalists. “. Careful here. There is a lot of space between the proposition “democratic governments should regulate new technologies in the public interest” and “governments should choose which new technologies are deployed”. The argument for gatekeeping regulation is not that governments are better at picking winners, but that nobody else can protect the public interest at all. You can polemically pick examples of governments getting it right on technology (radar, the GSM phone standard), governments getting it wrong (concentrating solar power, fusion) and of successes down to pure luck (the WWW). All parties in this debate need to practice cognitive humility.

One very improbable model is the British Parliament of 1714, which set up the Longitude Prize of up to £20,000. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Longitude_rewards This was not a triumph of democracy – Britain was ruled by a bunch of corrupt and grasping landed oligarchs. They did take the trouble to understand a difficult problem, recognize its importance, and take advice from the best scientists around, Newton and Halley. The oligarchs got several important things right: a very serious financial incentive (£20,000 was a duke’s income), partial awards for partial progress, neutrality as to methods (they did not pick a winner as between astronomy vs. chronometry), and a long-term commitment (an Act of Parliament not a reversible royal decree.) The watchmaker John Harrison cracked the problem in 1759, after decades of effort. He then needed more years of effort to claim the prize. Another nice touch is that the prize was open to foreigners. The Swiss mathematician Leonhard Euler got a modest award for a contribution to the astronomical method.

So let a hundred flowers bloom - in a well-weeded walled garden protected from Peter Rabbit and other predators.

(Cross-commented from jq.com.)