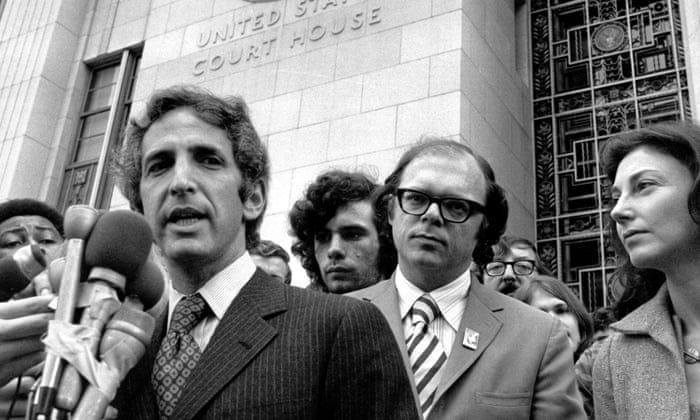

Daniel Ellsberg has died, aged 92. I don't have anything to add to the standard account of his heroic career, except to observe that Edward Snowden (whose cause Ellsberg championed) would probably have done better to take his chances with the US legal system, as Ellsberg did.

In decision theory, the subsection of the economics profession in which I move Ellsberg is known for a contribution made a decade before the release of the Pentagon papers. In his PhD dissertation, Ellsberg offered thought experiments undermining the idea that rational people can assign probabilities to any event relevant to their decisions. This idea has given rise to a large theoretical literature on the idea of 'ambiguity'. Although my own work has been adjacent to this literature for many decades, it's only recently that I have actually written on this.

A long explanation follows. But for those not inclined to delve into decision theory, it might be interesting to consider other people who have been prominent in radically different ways. One example is Hedy Lamarr, a film star who also patented a radio guidance system for torpedoes (the significance of which remains in dispute). A less happy example is that of Maurice Allais, a leading figure in decision theory and Economics Nobel winner, who also advocated some fringe theories in physics. I thought a bit about Ronald Reagan, but his entry into politics was really built on his prominence as an actor, rather than being a separate accomplishment.

The simplest of Ellsberg's experiments is the "two-urn" problem. You are presented with two urns. One contains 50 red balls and 50 black balls. The other contains 100 black or red balls, but you aren't told how many of each. Now you are offered two even money bet, which pay off if a red ball is drawn from one of the runs. You get to choose which urn to bet on. Intuition suggests choosing the urn with known proportions. Now suppose instead of a bet on red, you are offered the same choice but with a bet on black. Again, it seems that the first urn would be better.

Now, on the information given, the probability of a red ball being drawn from the first urn is 0.5. But what about the second urn. Strictly preferring the first urn for the red ball bet implies that the probability of a red ball being drawn from the second must be less than 0.5. But preferring the first urn for the black ball bet implies that the probability of a red ball being drawn from the second must be <em>more</em> than 0.5. So, there is no probability number that rationalises these decisions.

The title of Ellsberg's paper was "Risk, Ambiguity and the Savage Axioms". As a result, the term "ambiguity" has been applied, in contradistinction to risk, to the case when there are no well-defined probabilities. But this was not the way Ellsberg himself used the term. Rather he referred to

the nature of ones information concerning the relative likelihood of events. What is at issue might be called the <em>ambiguity</em> of this information, a quality depending on the amount, type, reliability and unanimity of information, andg iving rise to one's degree of confidence in an estimate of relative likelihoods (emphasis added)

I've developed this point in a paper whose title Seven Types of Ambiguity is one of numerous homages to William Empson's classic work of literary criticism. Among these homages, I'd recommend the novel of the same name by Australian writer Elliot Perlman (later a TV series).

The central claim in my paper is that all forms of ambiguity in decision theory may be traced to bounded and differential awareness. If that sounds interesting, you can read the paper here. If you're super-interested, I'll be presenting the paper in a couple of conferences in Europe in July - email me at j.quiggin@uq.edu.au for details.

This is an insightful synthesis - congratulations. Over the week, I was holding a workshop in Kathmandu looking into sources of policy failure in agricultural development in South Asia. I stated that it all boils down to ambiguity. While we conveniently blame politicians and corrupt behaviour for failures in public policy, rarely we examine the sources of such behaviours.

When I was charged with producing briefs to ministers of the day, a clear rule was to reduce the ambiguity - to ensure that it cannot be understood in different ways. When ministers were considering responses to resource management issues, such as biodiversity, water and climate, that was nearly impossible. Despite that we made significant progress.

It is safe to assume, as your work suggest, the nature of uncertainty remains uncertain and we will never fully comprehend nature. As a person born in to a buddhist family, I was introduced to that notion of uncertainty from early days and understanding the context in which we lived gave me scope to progress. The question in my mind is whether the central economic theory based on preferences is merely a smokescreen and the influence of new information on beliefs, and values that transcend beliefs into motives of action under the pressures of necessity for the impoverished and the convenience for the affluent could offer useful insights to public policy? Looking forward to further insights.

Pee Dee has said the bulk of what I would have said. The persecution of people rightly doing their civic duty and reporting very serious crimes has worsened but I can understand why, today, there is such s fortress mentality with the oligarchy