Australia’s banks are not a source of economic dynamism but a drag on our economic and social welfare

My latest piece in The Guardian

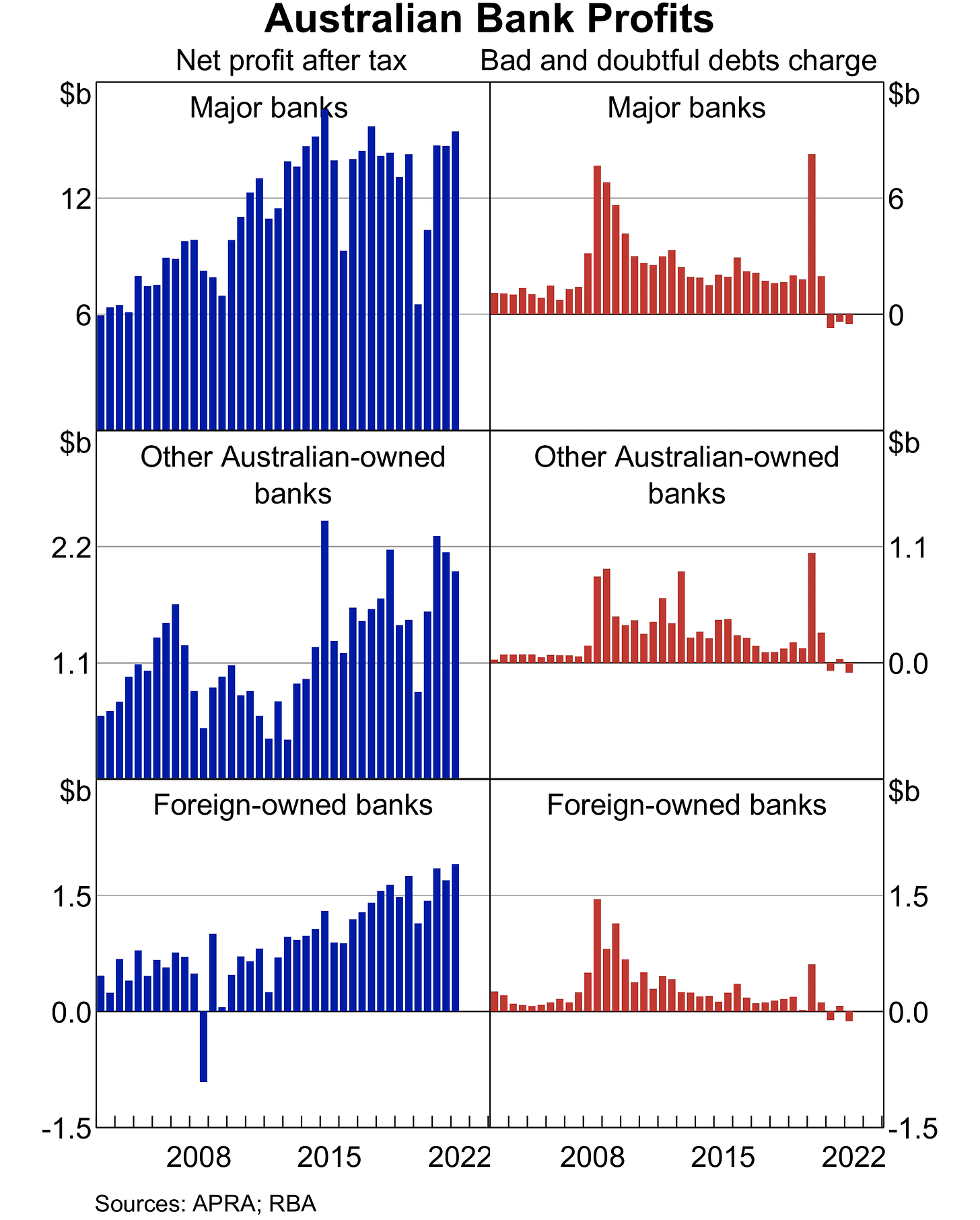

The announcement, by the Commonwealth Bank, of a $9.7 billion profit for 2021-22, with similar announcements expected from other major banks, is unlikely to be received well in the community. After being told to expect stable interest rates at least until 2024, mortgage borrowers have been hit with a string of increases in the Reserve Bank cash rate, rapidly passed on by the banks. A small reduction in the Commonwealth’s margin between deposit rates and lending rates was not enough to prevent a 9 per cent increase in profits.

But is this just griping about a necessary part of our economic and social system? Are the banks, and the financial sector as a whole, making a contribution to the working of the economy that justifies their handsome profits and the high salaries paid to managers and senior employees in the sector.

The Australian Treasury certainly thinks so. In a 2016 report on the then-booming ‘Fintech’ sector, Treasury stated

Australia’s financial services sector is the largest contributor to the national economy, contributing around $140 billion to GDP over the last year. It has been a major driver of economic growth and, with 450,000 people employed here, will continue to be a core sector of Australia’s economy into the future.

Recent failures in the Buy Now, Pay Later business have taken some of the sheen off fintech. But there is no sign of a change in the view that the $140 billion spent on financial services in Australia represents good value for money.

Retail customers might well disagree. The last really big innovation in the range of products provided by the banking sector was the introduction of credit cards in the 1970s. Most subsequent innovations (foreign currency loans, honeymoon rates, BNPL) have been little better than confidence tricks, leading people to take on more debt that they can afford, with the true costs hidden from view. Of course, there have been big technological changes resulting from the rise of the Internet, but the cost savings from these changes haven’t flowed through to consumers.

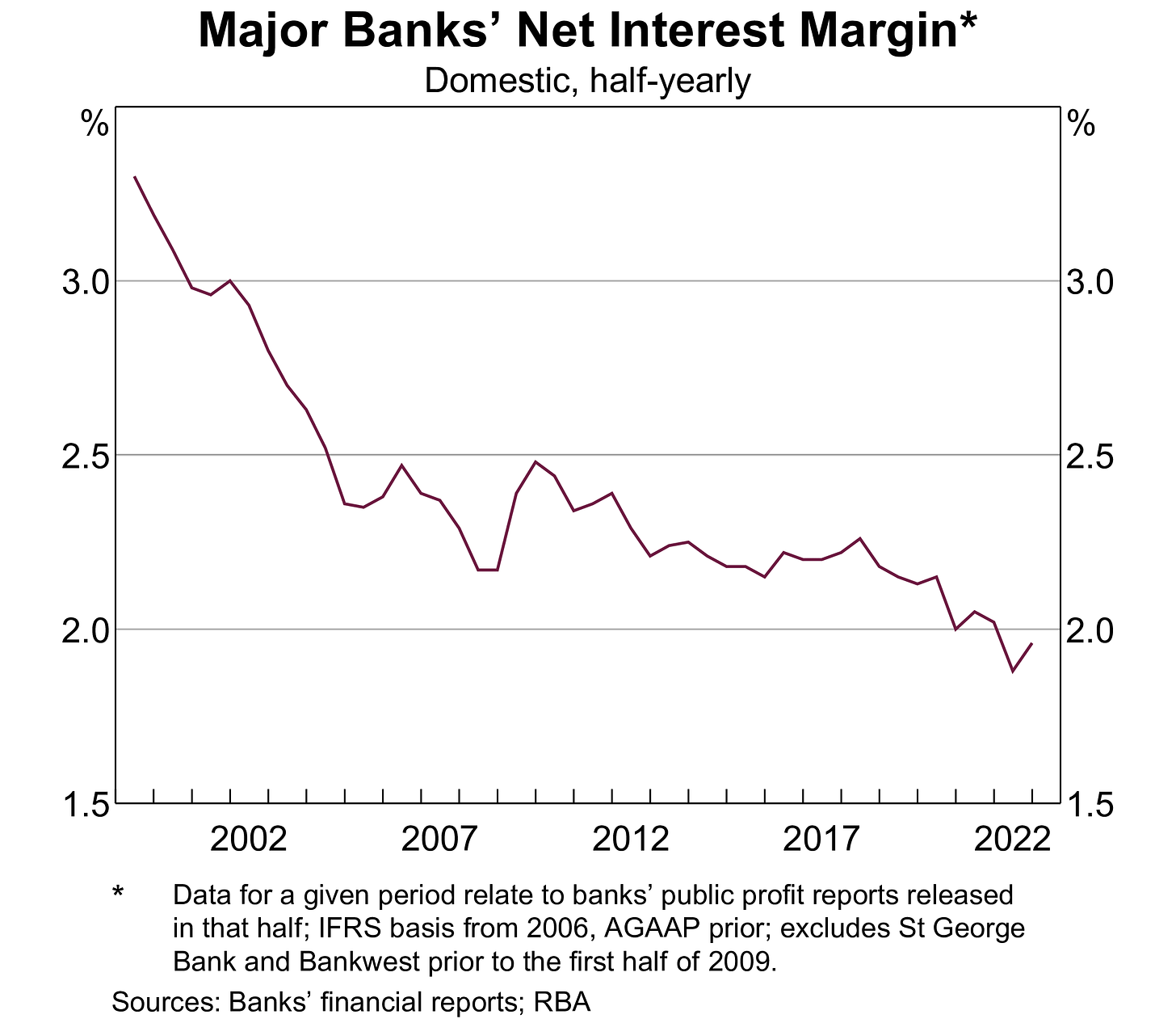

Bank margins have fallen somewhat over the past 20 years as can be seen from this Reserve Bank’s. But expressing the margin in percentage point terms obscures the fact that the size of the average mortgage has increased much faster than average wages or prices in general, which determine most of the bank’s operating costs.

The margin does include an allowance for bad debts, which would be expected to grow in line with the total amount of debt outstanding. But the banks’ losses from bad debts are tiny in relation to their profit margins, and are almost entirely associated with business failures in periods of economic crisis. The rate of foreclosures and mortgage repossessions is tiny - as low as 0.1 per cent of all loans in most years.

But while mortgage and deposit rates are what concern most of us directly, the central claim made in support of our massive financial sector is that, thanks to the deregulation of the 1970s and 1980s, the financial sector has been a major driver of economic growth. According to the claims made in support of deregulation, a dynamic financial sector will increase both the rate of business investment and the efficiency with which investment is allocated.

A central implication, which has formed the basis of public policy for the last three decades is that governments should get out of the business of capital investment and ownership. This claim has motivated privatisation, public-private partnership and the perceived urgency of reducing gross public debt.

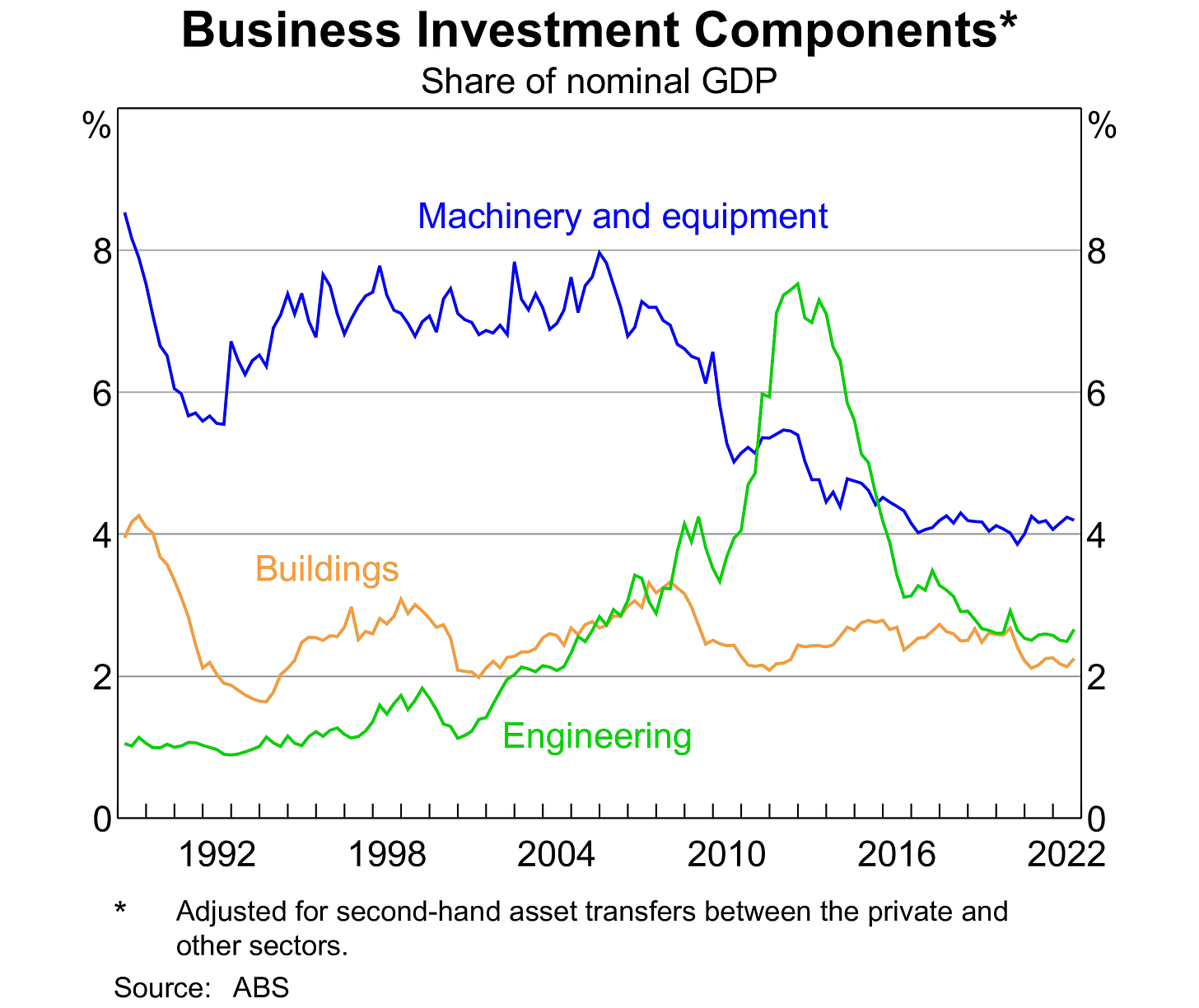

Sadly, there is little evidence to support this claim in Australia, or elsewhere in the world. With the exception of a brief spike in engineering investment during the mining boom, business investment has been declining steadily since the advent of financial deregulation.

There is no evidence that the allocation of investment capital has improved. The much-touted ‘productivity miracle’ of the 1990s disappeared long ago. According to the ABS, capital productivity has actually fallen, declining by 20 per cent since 1995. It is only the steadily declining price of (almost entirely imported) computing and communications technology that has prevented even poorer economic performance.

It is one thing to point out that the financial sector is not contributing as much to the Australian economy as it takes out. Unfortunately, it’s quite another to fix the problems, enmeshed as we are in a dysfunctional global financial economy. At a minimum, though, it’s time to recognise the financial sector as a drag on our economic and social welfare, rather than as a source of economic dynamism and policy guidance. Policies that reduce its size and profitability are more likely to beneficial than otherwise.

Why would banks fund risky business expenditure when they can simply keep the housing ponzi going? If we made housing less attractive tax wise they'd have to start investing elsewhere. It would help society enormously.

A few years back I thought the financial sector had got so big it was actually ‘crowding out’ the market.