Australians should be angry about Coles’ latest billion-dollar profit. But don’t blame the cost of living

Politicians will declare war on ‘cost of living’ and pundits will argue about inflation. The real point is the profits come at workers’ expenses

The latest massive $1.1bn profit reported by Coles will doubtless produce a new round of hand-wringing about the “cost of living”. Governments will produce initiatives aimed at capping or reducing prices. Pundits will use a variety of measures to argue as to whether such measures are inflationary. Then there will be debates about whether splitting up Coles and Woolworths into smaller chains would enhance competition. And the Reserve Bank will be encouraged to push even harder to return inflation to its target range.

But these responses, focused on the cost of goods, miss the point. Coles and Woolworths have increased their margins, yes – but prices for groceries have increased broadly in line with other goods. The real driver of supermarket profits is their ability to drive down the prices they pay to suppliers.

But the input that matters here is labour and it is here that the supermarkets are making big gains at the expense of their workers. Across the board, wages have failed to keep pace with prices over the last five years or more.

At least for the supermarkets, this won’t change any time soon.

In its annual wage review in June, the Fair Work Commission announced a 3.75% increase to the minimum wage and minimum award wages. But the increase barely offsets the almost identical 3.8% increase in consumer prices since the last review, leaving real wages unchanged.

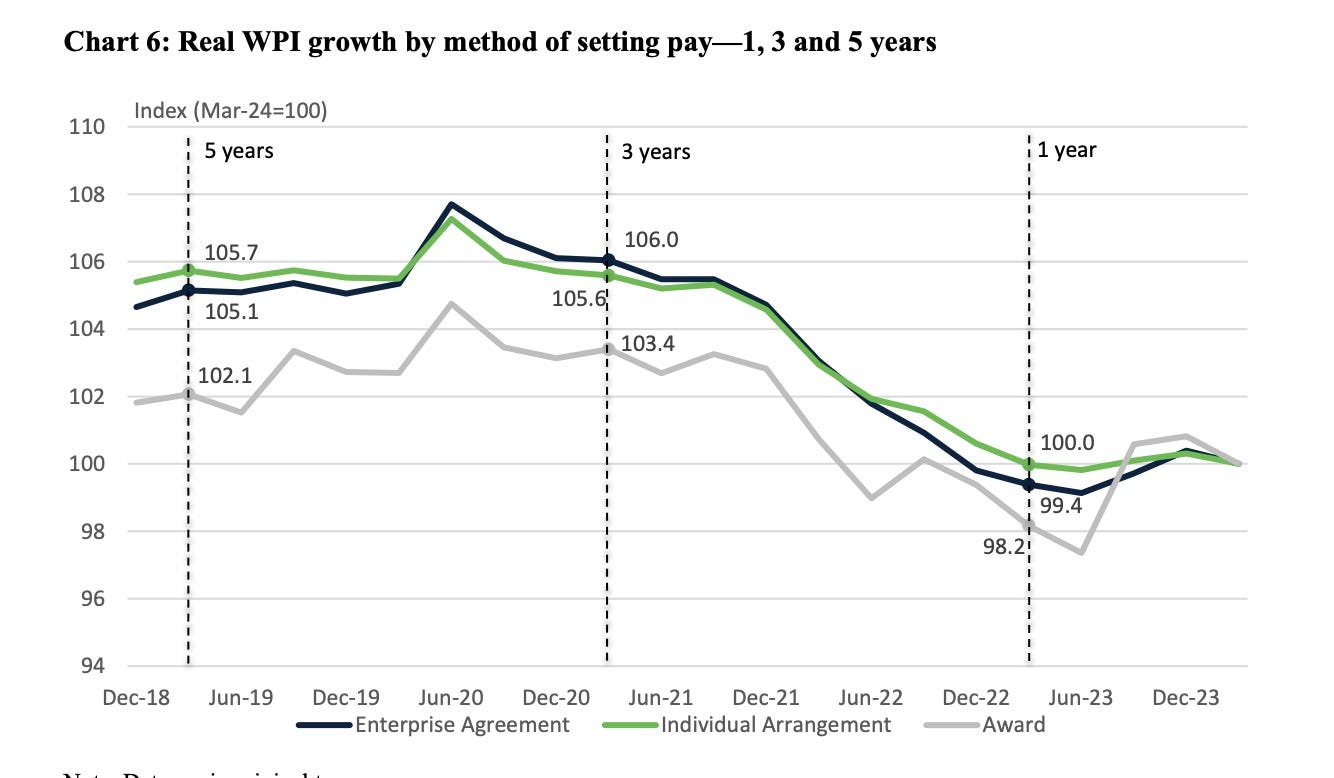

Yet again, the FWC declined to do anything about the fall in real wages that has taken place since the arrival of the pandemic, compounding a long period of stagnation before that. As it noted: “Despite the increase of 5.75 per cent to modern award minimum wage rates in the AWR 2023 decision, the position remains that real wages for modern award-reliant employees are lower than they were five years ago.”

Real WPI growth by method of setting pay – 1, 3 and 5 years. Photograph: FairWork Commission

There is no cost of living crisis for those whose income derives from profits. Those at the top end of town have seen their incomes soar. But even more modestly wealthy recipients of capital income are doing well, a fact reflected in their spending patterns.

This divergence is almost invariably framed using lazy generational cliches, comparing the expenditure of older and younger generations.

To be sure, old people, such as self-funded retirees, are more likely to be receiving capital income and less likely to be reliant on wages to pay mortgage interest. But this is by no means universal. Plenty of baby boomers are still in the workforce, while some of our most prominent property owners (such as Tim “avocado toast” Gurner) are much younger. Focusing on age merely confuses a debate that is already complicated enough.

The policies of the Reserve Bank make matters even more thorny. The problems here start with a dogmatic adherence to a 2% to 3% inflation target. The rationale for inflation targeting is thin, and the choice of target range is entirely arbitrary, arising from an ad hoc decision by a right-wing New Zealand finance minister in the early 1990s, one which was followed by a long period of economic decline in that country.

The dangers of using high interest rates to achieve rapid reductions in inflation, evident from the “credit squeezes” of the 1970s and 1980s, are now becoming apparent, as the drive to reduce inflation is reflected in a push to squeeze demand and prevent any recovery in real wages.

There is little hope that all of this will change any time soon. The concept of “cost of living” is simple and intuitive, even if it is highly misleading. What really matters is the purchasing power of people’s disposable incomes. But that’s a bit too hard for our political class to think about, let alone explain to the public.

Follow me on Mastodon or Bluesky

Read my newsletter

Just a reminder that these inflation targets are a made up number based on a throw away line in a TV interview with an NZ Finance Minister.

https://time.com/6548908/inflation-target-federal-reserve-essay/

"In the late 1980s, the New Zealand central bank like most central banks worldwide had worked assiduously to bring down the double-digit inflation that afflicted many developed countries from the mid-1970s until the early 1980s. When asked in a television interview what he thought should be a sustainable, healthy level of inflation, the New Zealand finance minister stumbled for a moment and said that it should be around 1%. That was then refined by the bank staffers to 2%, which was officially adopted as a target in the 1990s by other central banks ..."

The plight of the cost of living created by corporate price gouging, making lives difficult and expensive, driving austerity and difficult choices, rendering people impoverished and even homeless. The wealthy baby boomers you refer to with safe & large incomes no doubt, like Marie Antoinette, would cry mockingly, “Let them eat Cake!”

“The ABS does produce cost of living indices which consider the cost of living according to your source of income – wage, pension, or government benefits“, stated the Guardian’s Greg Jericho some years back now. Once you add the real cost of living factors, you will quickly realise real wages are not keeping up with the actual costs of living.

Despite small wage growth, these rates are less than both inflation AND productivity, both of which have expanded in recent years, by all indicators. One would assume if the nation is being more productive that wages should rise accordingly. Instead real wages have fallen! Your purchasing power is roughly the same as it was a decade ago (despite nominal wage rises) because of inflation. Prices having been brought up are not going down. There is no sign of deflation and housing costs are getting worse. REAL inflation which should include housing costs which would render a far larger CPI increase measure! CPI fails to account for substitution, and it also fails to factor in the price of housing and the cost of financing. Let’s face it: if they included the cost of financing (thanks RBA), guess which direction inflation would be headed in? 🤔